OX – Intervention in Cologne, 2017

Ever fascinated by the street for its experimental potential, OX has spent decades developing a style unlike any other. Known as a billboard hijacker, he has been pasting his collages and designs all around Europe, aiming to draw attention to a different kind of urban aesthetics. His strong, schematic and colorful images are infused with a good dose of humor, without ever turning banal. Still, these street actions remain only the crown of OX’s elaborate studio practice that precedes every one of the hijacks. When faced with his work, people can hardly look away and that is exactly the point – to keep an interested eye on the picture long enough to stimulate the brain into thinking. With every image, OX invites to reconsider our environment and its looks, and he does it so effortlessly and with such elegance that a person is always entertained, often inspired and never annoyed. It’s a special skill this experienced French artist has and we enjoyed the opportunity to talk with him about his own art history and the emergence of his unique visual language.

OX pasting

Looking Back to the 80s

You have started creating public art before street art took shape. How would you compare the situation in street art then, in the 1980s, to what we have today? What about the global situation, then and now?

When I started to paste paintings on billboards, there were already many shapes of artistic action taking place in the streets (stencils, graffitis, posters…). But this kind of artistic expressions was still marginalized by cultural institutions and the broad public. Thus they were not considered a part of a movement, even though journalists and galleries were becoming more and more interested in them, especially in the USA. In the 1980’s, when we worked with the Frères Ripoulin collective, we were not making the difference between pasting in the street, publishing fanzines or exhibiting in galleries. Our influences came from pictorial and graphic movements such as Figuration Libre and Bazooka, rock, comics, underground culture. One specific action which gathered all of these influences and best illustrates that period was the “live painting” which took place during concerts. We talked about art for all or media-painters, sometimes about art in the street… During all these years, many people have intervened in the public space and the phenomenon has only grown.

The real breakthrough came with the Internet and the fact that artworks that were first and foremost recognized as such by a few enthusiasts found themselves at the heart of a mainstream and viral culture. This has created an emulation between artists and led to the emergence of numerous initiatives and trends. This has been very beneficial for many artists, including myself because it has given me more visibility and encouraged me to persevere. Nowadays, what we call “Street Art” covers so many different practices and conflicting goals that it is impossible to define: what does a tag have in common with a public or private commission, except to be seen in the same space? A whole system has developed that uses the street without taking into account its specificity. For some, this consists in developing a gimmick and repeating it over and over again, using public space only as a springboard to access the art market without really understanding its experimental interest.

I’m not very interested in this globalized dimension of imposing ever-more virtuosic and gigantic visuals. On the other hand, I think that there is a real popular art that is still alive and that if these practices persist it is because they represent a space of freedom that everyone can seize.

Over the course of your long and dynamic career, you have worked in different media, often paper-based, but you have also witnessed many new movements and styles emerge and develop. How did you come up with the method you are using today?

In the beginning, I essentially used kraft paper, cheap and very convenient for collages. It was also used as a material to exhibit in the galleries. The painting technique was the same inside and outside: acrylic for large flat tints, fluorescent colors, large black rings as in comic strips and sometimes spray paint for rough shadows. Today I still use the same materials for collages on advertising boards, but the techniques I use for exhibition pieces are more diverse. I often use a rather elaborate manufacturing with a lot of wood cutting. So, the materials I use vary. As far as the visual aspect is concerned, despite the differences in treatment, I try to bring out a form of coherence in the permanent coming and going between these two activities which feed and influence each other.

How did this help shape your visual language?

My graphic language, at first very close to punk-rock fanzines, changed radically when I switched to 4- by 3-meter posters because I had to adopt a language with an impact as powerful as that of advertising. The shapes have been simplified, purified by taking more and more distance with the figuration. What came first with our collective were the actions and reactivity, not the formal reflections. It was at the dissolution of the group that I really started to confront myself with the question of “what to paint?”. I realized that what mattered to me were the aesthetic emotions caused by the assemblages of shapes and colors. The choice of the subject was finally quite secondary. So, I subtract, hide, cut and so I practiced a sort of reverse Pop Art, while I kept only what didn’t make sense from the commercial imagery: the model, the backgrounds emptied of their contents, the hidden texts…

OX – Intervention in Cologne, 2017

Billboards and Inspirations

In your biography, you mention that “discovering Keith Haring” was a real turning point for you. How did his art influence you? When was this?

It was, of course, a graphic shock, but he seemed to tell us “go ahead, act now”. He confirmed the intuition that we had to start without waiting to accumulate more knowledge or to pass diplomas. He was in tune with the music we were listening to and had the same desire to spread his art throughout society. It was much more than an artistic influence.

“Billboards are like huge windows, oversized paintings, hanging in the city,” you said. What is it about billboards that inspires and fascinates you so much?

It is true that we used the advertising panels to recreate a kind of outdoor exhibition, a giant gallery accessible to the greatest amounts [of people], but also as a means to make us known. We put a telephone number on the poster itself so that we could be contacted by the press journalists who made the link with the galleries. They were very fond of this kind of action because it seemed totally new.

Did your inspirations change over time? What inspired you then and what does today?

The French movements I spoke about before, which were linked to rock culture, but also pop artists such as Lichtenstein. Comic magazines but also the satirical press which conveyed a spirit of rebellion and derision sometimes inspired by Dadaism. In general, popular culture with a particular interest in kitsch and the bad taste that accompanies it. We were in opposition to conceptual art and very resistant to an intellectual reading of our activities. Then, I came closer to a more minimalist and abstract research and even if I learned to like other artists I remain much more inspired by the places of consumption and entertainment than by the places of culture. My studio work often stems from a contextual approach in an urban setting rather than from museum attendance.

OX in his Studio

OX – A Studio Painter

What does your creative process look like, from the idea to the installation? Do you spend more time in the studio or outside, in the streets?

I am a studio painter even if I spend a lot of time outside, especially for spotting and shooting. The main part of my time is occupied by painting and by the computer simulation work which precedes it. I hardly ever paint on the street. On the other hand, I like very much the moment of the collage where I meet all the risks related to the public space, the confrontation with the reality of the material and of the space which surrounds it and the part of unforeseen which arises. It is a free and gratuitous act that brings me back to the origins of my commitment.

What does it take to prepare to go out and paste your work on a public surface?

A lot of work before to find a spot, a lot of simulations to check the validity of the intervention, remove all that is superfluous and that could harm the desired effect when confronting the painting with its environment. Some material (stepladder, seal, brush, perch) but the pasting process itself is very simple.

You create work in the studio and in the public space, but only one of those is ephemeral. How do you feel about the temporality of your publicly installed billboard covers?

I am comfortable with the disappearance of the paintings covered by the advertisements, I like very much that things return to their state of normality (even if I would sometimes prefer that this period last a little longer than the usual 4, 5 days). I have much more difficulty with the durability of the artworks which must demonstrate their ability to function on a white wall and which must be protected, packed, transported. It means the artworks for which one can ask explanations or even justifications in order to prove the appropriateness of creating such or such things. It turns out that photography is the last stage of interventions in the public space, so I have a trace of this ephemeral moment.

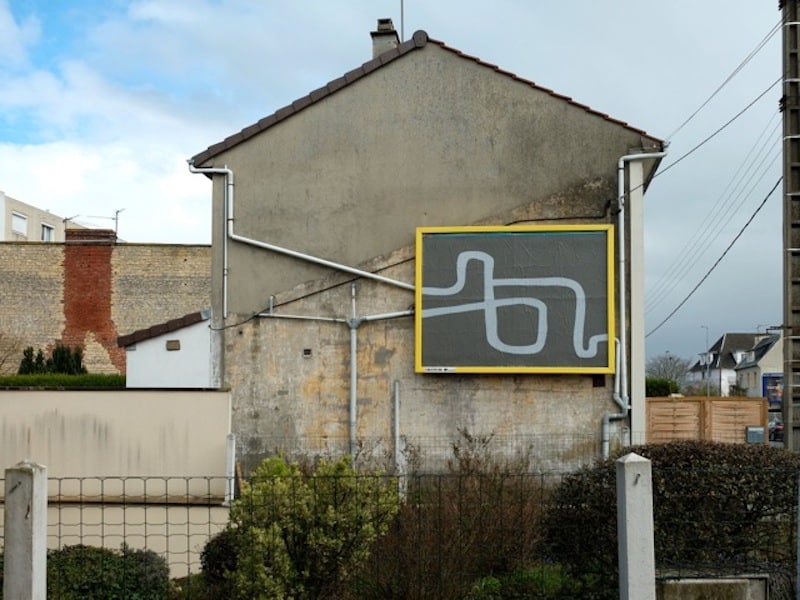

OX – Billboard in Caen, March 2018. Courtesy OX.

What is More Normal Than Pasting a Poster on a Billboard?

Do you remember the first billboard you hijacked?

I sometimes hijack advertising images, but usually, I hijack the medium (the billboard itself) from its primary function (which is to deliver a commercial message).

I cover the entire surface so the interaction occurs more with the environment of the billboard than with the image it shows. The first time was in Paris in 1984, but as I didn’t take into account what was around I’d rather talk about the last time. It was in Caen in March 2018, a billboard fixed on a wall on which water drain pipes were hung. I chose this spot because of these pipes and I knew that I would play with them.

This game obviously consisted in making the pipes intertwine visually but what I like in the end is that it looks more like a small abstract pattern and that we can easily omit to make the connection with the pipes. In fact, the choice of this location was the pretext that led me to conceive this pattern.

In one article from 2013, it says that you have never been caught while illegally installing your work on billboards. Did this change since then?

Yes, it is still true. I intervene during the day and what could be more normal than someone who sticks posters on a billboard?

OX Billboard Project in Cologne – Artist in action

Freedom from the Political

These days we see a lot of activism in the streets, one of them coming with the adbusting movement. You have several times mentioned that your work is not the exact opposition to advertising, but rather a contemplative alternative that changes the environment. (“My work it is not about decorating the city, but rather about creating a very small moment that is just a little different. It is a question of moving away from the relationship between the slogan and the idea of selling, in order to integrate them even more in the moment. This is not to cause the fall of advertising,”) In terms of social and political context, where would you position your work?

I affirm my right not to position myself ideologically by spreading explicit messages.

I define myself as a painter and I claim the possibility of painting bouquets of flowers if I feel like it without being blamed for a lack of political awareness. I think that my illicit activity of direct expression makes sense. It has a philosophical and poetic conscience. I am not advocating the disappearance of advertising, I am interested in it because it is part of the popular culture and I even use its vector of communication on a personal basis. However, I refuse to put my work at its service and I am very critical about its harmfulness. So I have no state of mind to make some of them disappear.

You mention that the Internet influenced your work in a good way. In what way did it bring positive changes to your practice? How do you use the web today?

The Internet has allowed me to meet new people and broaden my field of action enormously. Finally, it allows me to concretize things that would have remained virtual.

In 2017, you did a big project in Cologne, with ten billboards. Are you planning a project of similar scale in the near future?

It was an authorized project in connection with Kölner Liste. I was curious to work legally with a billboard company. The interest of this kind of project is to have a logistic support which allowed me to realize a great number of collages. If this doesn’t fundamentally change my approach as to the final result, it still creates a strange and contradictory situation by the fact that I was not covering random advertisements, but a picture of my work used to promote a contemporary art fair, how confusing! So, why not, but without authorization, it will be even better!

This interview was given in French. Please, find the French version HERE.

Translation from French: Anaïs Raulet

All images (except billboard in Caen): Thomas von Wittich