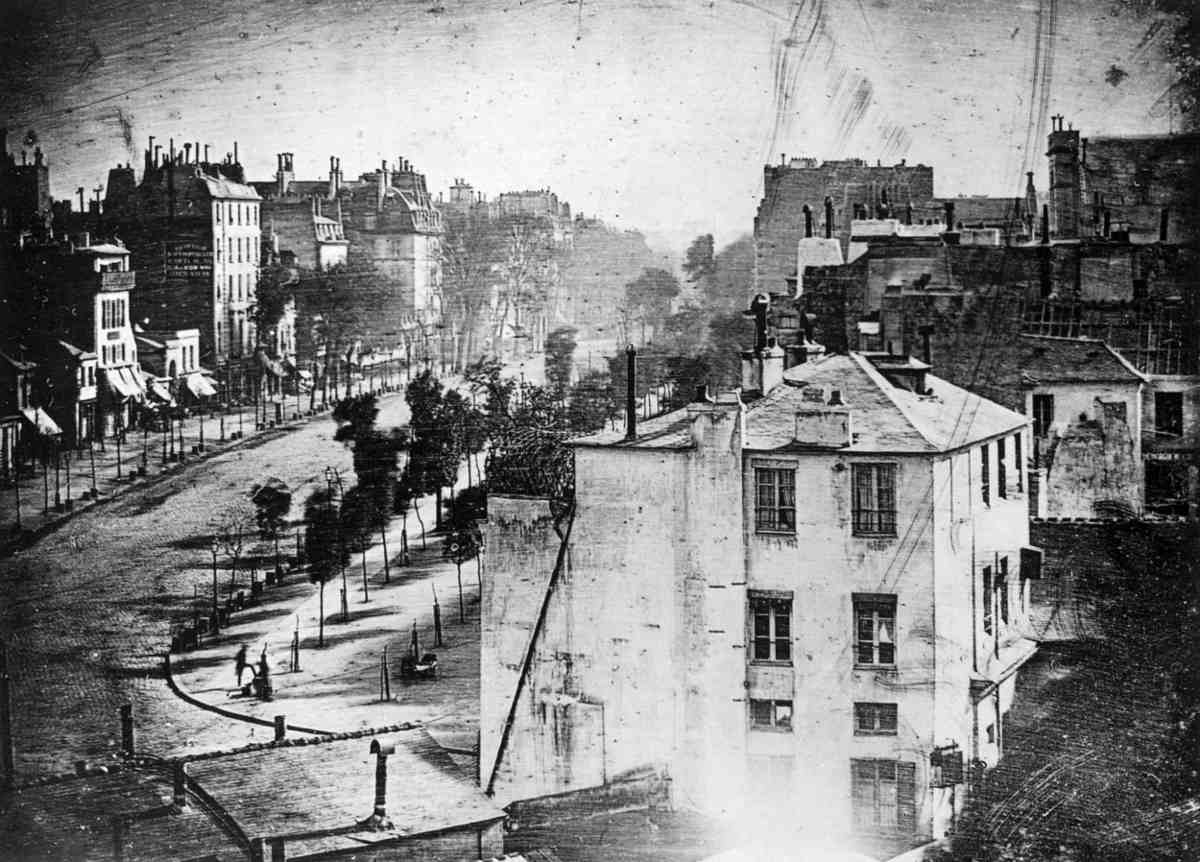

Louis Daguerre – Boulevard du Temple, 1839 – Image via wikimedia.org

In all of art history, it’s a challenge to find a term or a genre name that is as deceptively simple as street photography – this subgenre of photo making proved to be one of the most adaptive and malleable techniques of the last two centuries. Trying to strictly define this type of photography actually does injustice to the liberty and non-uniform nature of the style, but in an attempt to do so, one may be correct to claim it’s a genre of photography whose pieces present an opportunistic interaction between a photographer and an unsuspecting urban public space. Over the years, many misconceptions and theories related to street photography emerged, concerning a range of its aspects, including style, rules and goals, as well as the general validity of the style. The largest misunderstanding, however, is the one that seems to make the most sense – on the contrary to popular belief and the very name of the genre, this type of photography does not need to be taken on the actual street. It can still be a valid picture of this kind if it’s taken indoors, as long as it’s a public environment in which one captures shots of bypassers and regular surroundings, hunting the exact moment in time when the ordinary becomes extraordinary. Here, we will attempt to define what street photography is, explain the history it went through since its conception and will connect it to its younger, more strict sibling of urban art photography, one of the most popular photographic subgenres to date.

Dennis Stock – Venice Beach Rock Festival, 1968 – Image via filmsnotdead.com

What is Street Photography?

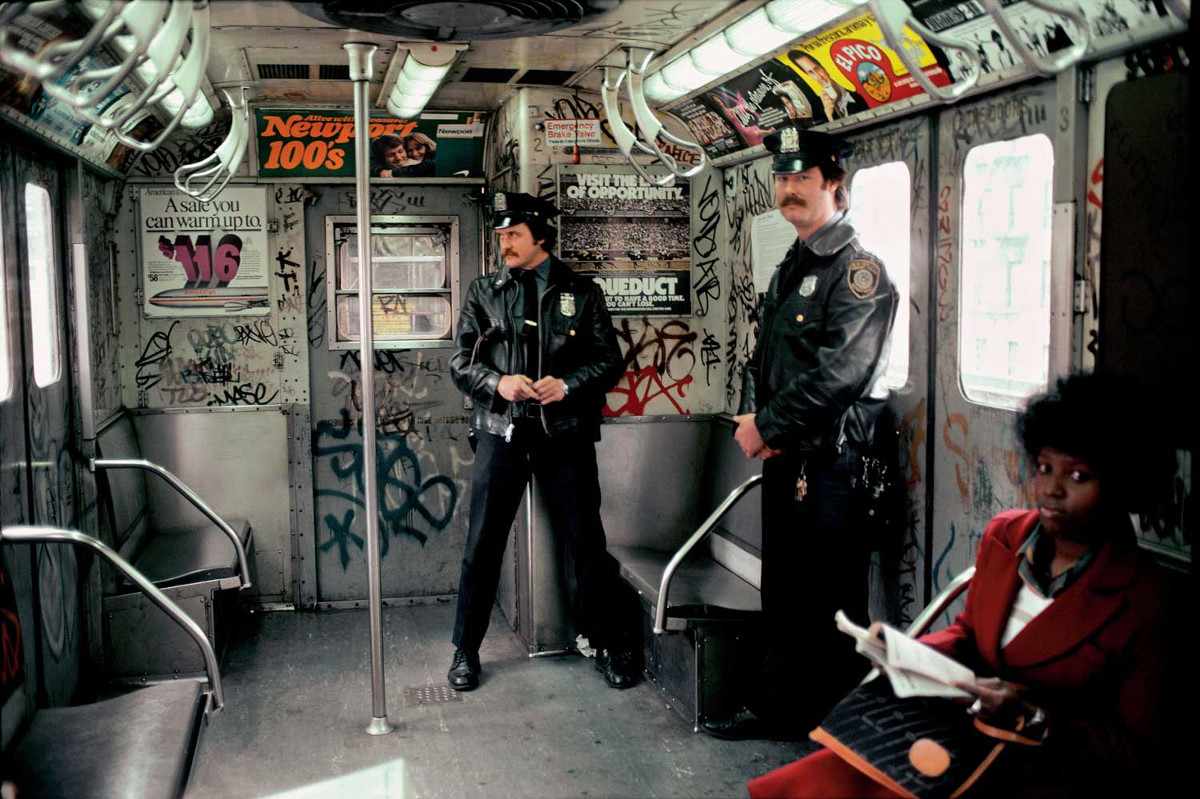

This particular genre of fine photography is probably best explained as an opportunistic moment in which a photographer captures a candid public scene in front of him. As was explained before, although there is the actual word street in the very title, this technique does not really tie itself to only pavements and alleys – in order for a street photo to be genuine, it has to feature an unposed situation within a public place, regardless of where that place may be. It can be the street, yes, but it can also be a bar, an inside of a train, a football match, cinema or a factory – it can be wherever you desire to take it and this is considered to be the most flexible aspect that gave street photography the reputation of rich variety and artistic freedom.

Another common misconception is that this genre requires the presence of people in order to be genuine. Although this may seem logical and does make some sense, street photography might be totally bereft of people and can simply be an image of an object or environment that caught the eye of the artist.

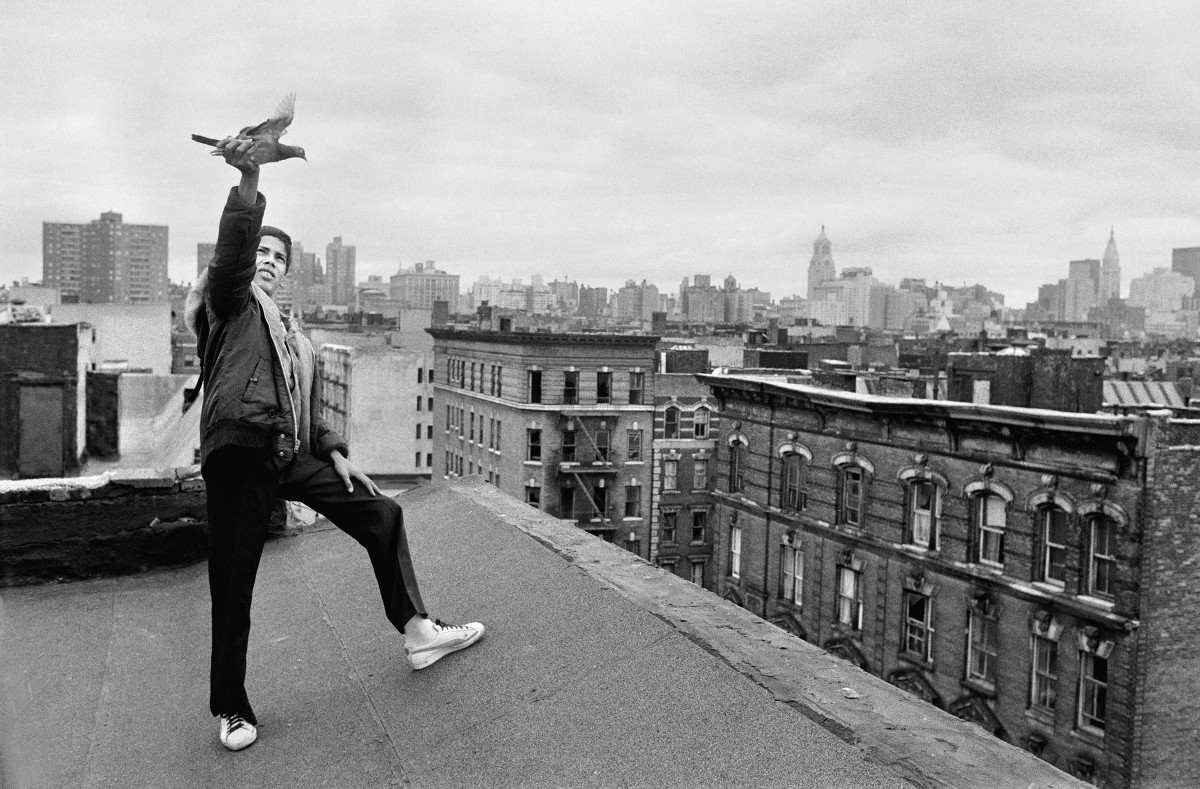

Martha Cooper – An Untitled Photo – Image via alldayeveryday.com

However, street photography seems to have one strict rule, which has been broken in a couple of instances even by the greatest names in the genre – it should be a true mirror of society, an unmanipulated scene with unaware subjects and unstaged settings. This is why street photography is often described as the most honest creative form ever invented as no amount of paintings, sculptures or films can rival the brutal honesty of just one good street photo. The magic of its chance interactions with everyday human activity within urban areas is undoubtedly the focal point of this genre and it falls second to nothing, not even the quality of the image or talent of the artist.

Through a trial-and-error method, a street photographer’s sharp eye needs to develop the most powerful artistic weapon of the medium – a knack for timing. The requirement for such an ability is a relatively new concept when you analyze history, as no artists before these kinds of photographers had mere seconds to make decisions that could either make or break a masterpiece. By improving timing, a street photographer is able to achieve his only goal – to communicate an objective impression of the experience of everyday life in a city.

Thomas Von Wittich – Vermibus (DissolvingEurope) – Image © Thomas Von Wittich

What Street Photography Is Not

In the attempt to fully grasp the term of street photography, perhaps the wisest approach is to explain what it is not. Due to the unmanipulated approach, street photography has often been associated with its big brother, documentative image making, a strict and disciplined technique from which street photography had big problems of emancipating. The difference between the two is that, unlike documentaries and their archive-like methods, the general content of the scene or its precise location are irrelevant to the field of street photography. Another discrepancy is that a true photographer of the street relies heavily on the timing and trial-and-error method, both of which are not suitable to a person who wishes to document something with their camera. A person interested in documenting someone or something is also motivated by the evidentiary value or socio-political function of the resulting shots – something usually not present in a mindset of a street photographer.

Another common and similar comparison is with the ideas of photojournalism, but a street photographer does not intend to illustrate a news story or other narrative, rather choosing to let go and see what fate is in store for him, whatever that may be. Although the documentary approach and photojournalism seem like the closest concepts to street photography, maybe that honorary mention should go to landscape depictions as they are also rather unmanipulated and unplanned. However, in order for street photography to be what it is, it needs to have a certain urban element to it, which is the very opposite of shots centering around lakes, sunsets and hills. Landscapes also have quite strict compositional rules whilst street photography has no such boundaries and literally allows any position or angle. Although this is not a valid comparison, some people have actually associated street photography with pictorialist photos, or Pictorialism. As wrong as this comparison may be, it allows us to emphasize the most important aspect of street photography – the main attribute of Pictorialism is extensive staging and preparing the subjects prior to taking their picture, whilst street photography insists on unmanipulated authenticity.

We should also note that this genre does not look kindly on interventions after the actual shooting, a technique commonly found in professional photography or films. After this extensive analysis of both what street photography is and isn’t, it’s quite obvious just how loose the nature of this genre is. It offers a true unfiltered reflection of both the artist’s intentions and coincidences provided by the calm chaos that surrounds us. The entire genre is all about reacting, observing and even endless stalking of the streets for opportunities – the latter is actually comparable and serves as a heritage to the bohemian ways of wandering the city, tirelessly seeking inspiration. It’s about letting go of control, about uncompromisingly committing to whatever comes in front of the camera, venturing into the unknown and limiting yourself to just observing and reacting. Not many styles and genres of art demanded such a lack of authority – perhaps Andre Breton came the closest to such freedom with his theories of automatic painting that were crucial for the development of Surrealism.

Jaime Rojo – Occupy Wall Street – Image © Jaime Rojo

Roots, Artists and History of Street Photography

Although street photography is a medium that is strictly associated with the 19th, 20th and 21st century, its roots can actually be found in literally every period of art before that time. For a reason open for discussion, human beings have constantly been interested in somehow depicting everyday public life that surrounds them – this was true from the very beginning of our history and pre-historic cave paintings. As civilizations started to slowly establish themselves, it is possible to notice the same themes of public places in all of them – Sumerian, Egyptian, Greek, Roman, etc. If we fast forward a couple of hundred years, we can see that this trend stagnated in the middle ages, as it mostly concentrated on religious depictions, although there were church scenes like the Triumphal Entry into Jerusalem and Ecumenical Councils that incorporated views of public spaces in which holy occurrences were displayed. This stagnation lasted until the time of Renaissance which rediscovered classical art, including the said motifs of depicting public spaces with everyday people in them – artistic movements that followed adopted these themes as well, including the likes of Baroque, Rococo, Romanticism, etc.

Gustave Caillebotte – Paris Street, Rainy Day, 1877 – Image via wikimedia.org

The Origins of Street Photography Art

As the 19th century was in full swing, we can notice true prototypes of contemporary street photography – as a matter of fact, the earliest surviving photograph of a real-world scene titled View from the Window at Le Gras is a shot of a street, taken by Nicephore Niepce in 1826. About a decade and a half later, in the year of 1838 (or 1839, as some experts believe this year to be the true one), the first photograph of figures in the street was recorded by Louis Daguerre as he pointed a primitive camera through the window of his studio in Boulevard du Temple, in Paris. This famous photo which carries the name of the street it depicts is also considered to be the earliest known candid photograph of a person and is the first notable image of its kind. As the years passed by, technology development allowed rapid improvements on the devices Louis Daguerre and other earliest photographers used – in 1851, Charles Negre managed to photograph people in movement on the street of the French capital and further technical sophistications allowed Eugene Atget to start his own series of Parisian people from the 1890s. Atget’s projects pushed the boundaries of street photography and the documentative approach in which he captured both people and architecture of the City of Light inspired many future similar series of other authors. There were signs of the medium emerging in England as well, as photographers such as john Thomson were documenting London in the 1870s and making the capture of everyday life on the streets a significant role for the young street photography. It is also important to note that the ideas behind early street reproductions were not exclusive for the artists who work with cameras – painters representing movements such as Realism and Impressionism focused much of their creative efforts on making pieces with compositions placed in public locations such as bars, streets and various views of cityscapes. Contemporary painters of the time like Gustave Caillebotte and Claude Monet authored pieces whose compositions and themes can easily be connected to today’s picture-taking. Paintings like A Bar at the Folies-Bergere (1882), The Cafe Terrace on the Place du Forum (1888) or Paris Street, Rainy Day (1877) are all genuine prototypes of modern street photography. It is crucial that you understand the following – fully grasping the term street photography means knowing how much connection there is between it and the rest of art history, as this medium is nothing more than a current reflection of the human desire to document the everyday life around it.

Nicephore Niepce – View from the Window at Le Gras, 1826 – Image via wikipedia.org

Artists of the Early 20th century

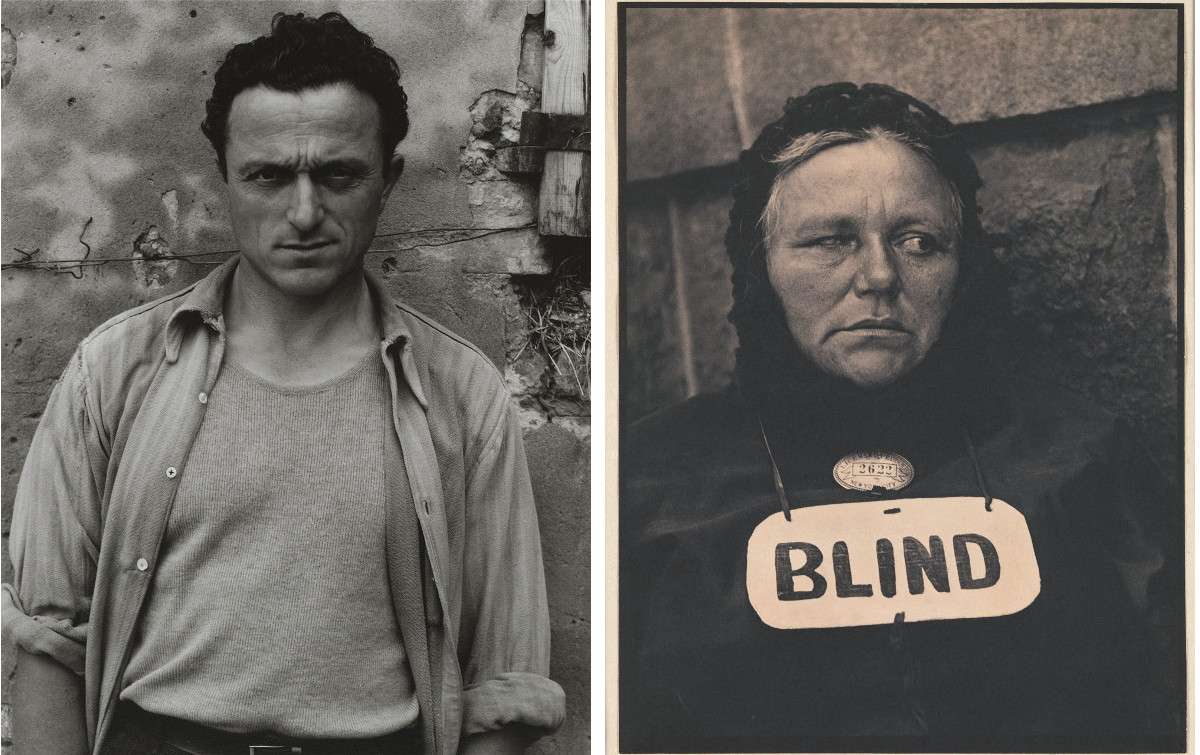

The beginning of the 20th century brought much optimism and technological development, whilst numerous art forms and styles were also starting to play a crucial social role. The reason why street photography as we know it today was not possible in the 19th century is that the long exposure time meant that the majority of people on the street that were present as the image was made were invisible in the final product. In our example of Boulevard du Temple, the only person who stood still long enough to register on the plate was a man who stopped to get a shoeshine. This all changed in the 20th century as photography with pedestrians in it actually became possible and cameras became a strong part of numerous avant-garde movements such as Futurism, Surrealism and Dadaism. Photography has been advanced incredibly and it was turned into an accessible medium that offers an interesting alternative to painting. And as the first genuine avant-garde movements were taking place around Europe, a selected group of artists chose to devote some or all of their attention to photo taking – street photography was but a subgenre and although it could not rival the popularity of other art forms at the time, it was still able to develop quite successfully and coalesce into a distinct form of photographic practice. This was the moment street photography emancipated itself and became an independent genre as every single one of the photographers before this period had other agendas in mind despite their works seemingly belonging to street photography. The seeds of this genre are also present in photographs by Alfred Stieglitz and Paul Strand, made in the late years of the 19th and early years of the 20th century. Stieglitz’s Winter, Fifth Avenue (1893) and The Terminal (1893) show quotidian scenes of New York City, manipulating snow and smoke to enhance the pictorial energy of the image. In photographs such as Wall Street, New York (1915), Paul Strand produced an image that illustrates the experience of scale in the city’s financial district while opposing the structural geometry of the architecture with the pattern of figures and shadows of the pedestrians on the sidewalk. Blind (1916) portrays a terribly common feature of urban life at the time – a blind beggar. It displays seeds of a relatively candid concept even though it is quite certain the woman knew she was being photographed. Thus, both Stieglitz and Strand made photographs on New York streets that contributed to the development of the genre despite the street photography not being their primary pursuit.

Paul Strand – Young Man, Luzzaro (Ivo Lusetti), 1953 (Left) / Blind, 1915 (Right) – Images via artblart.com and metmuseum.org

Interwar Period

In the years between the two World wars, several photographers had an immense impact on the subsequent maturing of street photography. As European artists were forced to take a step back while the war was going on around the Old Continent, the focal point of the genre was moved to the United States. However, in the mid 1920s, photographers around Europe began working yet again – Hungarian photographer Andre Kertesz’s images of Paris, made after he adopted the 35mm camera device in the year of 1928 (Meudon (1928) and Carrefour Blois (1930)), display how the metropolitan life of the French capital used to look like with a strong note of surrealistic concepts. Although Andre Kertesz is never considered a worthy rival to Brassai and Henri Cartier-Bresson, he heavily influenced both the styles and concepts of the famous duo. Brassai, whom Kertesz personally introduced to photography, became especially well known for his photographs of Paris at night which were an original concept at the time as no one prior to him even attempted to do such a thing. The solutions to troublesome shooting sessions in the dark were direct and primitive, yet perfect for what Brassai desired. He would focus a small plate camera on a tripod, open the shutter when ready and fire a flashbulb. If the quality of his light did not match that of the places where he worked, it was, for Brassai, even better, as it made the product more distorted, more mysterious. His images of the characters, sights and activities around Paris proved to be fundamental for street photography and who knows where the genre would end up if this Hungarian artist did not work at it. Kertesz was also a mentor to Cartier-Bresson whose concept of the decisive moment, explained as the instant when the subject matter and compositional form align, had a massive impact on street photography and its future course. His works such as Behind the Gare Saint Lazare (1932) also presented the viewers with everyday life in Paris, but unlike Brassai, Cartier-Bresson also took images during the day and he worked in other cities such as Madrid and New York. By explaining the idea of a decisive moment, Henri advocated for spontaneity and intuition as the driving forces of creative photography, which strongly impacted the street subgenre. The works of Brassai and Henri Cartier-Bresson fundamentally shaped the practice of street photography after World War II.

Brassai – Greestone Terrace – Image via emaze.com

Post-World War II Period

Logically enough, the immediate post-war years inaugurated a particularly rich era in of street photography in the United States, as this was the only country whose domestic cities were not exposed to warfare. Several key street photographers like Lisette Model, Helen Levitt, Louis Faurer, William Klein, Saul Leiter and Robert Frank authored some of their most renowned photos between the years of 1940 and 1960. Every single one of them brought something new to the table and helped develop the genre that was experiencing a significant rise in popularity in those years. Helen Levitt filtered decisive moments from city life into universal human images that were appealing to both the experts and the casual viewer. William Klein transformed sun glances into characteristicly grainy and even blurry compositions that embodied the frantic pace and aggressive rhythm of post-war New York City. Louis Faurer expanded on the Brassai concepts of night time shooting, concentrating on social circles ignored by the American mainstream. As of that moment, street photography had bragging rights of becoming a genuine and independent genre with numerous artists and notable appreciations. Although not as widely spread, street photography flourished outside the USA during the post-war period as well. In France, it was dominated by three artists: Robert Doisneau, Willy Ronis and Izis Bidermanas. Doisneau’s The Kiss (1950), a composition depicting a sailor excitedly kissing a woman in front of the Hôtel de Ville in Paris, became a symbol of optimism to which many aspired after the devastations and horrors of World War II. It quickly became one of the best-known photographs of the era. In the United Kingdom, Roger Mayne photographed everyday life of the working class streets where new cultural moments were being born, such as the appearance of the Mods, Teddy Boys, Skinheads and Rock ‘n’ Roll. Mayne’s images of these subcultures socializing around the alleys of London not only helped establish street photography in the UK but also played a crucial role in the generational tensions that would erupt in the 1960s. Working parallelly across the Atlantic, another photographer who must be mentioned here is John Szarkowski, an artist responsible for the establishment of the snapshot aesthetics, widely considered to be a prominent motif in American photography. By the end of the 1970s, street photography was a well-respected medium with a rich background and a genuine art form that was considered to be a worthy mention in any book of art history.

Robert Doisneau – The Kiss, 1950 – Image via onlyoldphotography.com

Magnum Photos and Their Extensive Series

After we’ve gone through the expansive history of street photo making, it’s the right moment to mention an organization dedicated to connecting the past and the present photography scene. This is, of course, Magnum Photos – an institution renowned for great diversity, owned and administered entirely by members who are all photographers themselves. Since the artists are the ones in charge, this makes Magnum Photos quite unique as they do not treat images as a product in a way usual corporations would do – instead, they treat it as a piece of art and show every single picture the respect it deserves. Working out of their four editorial offices placed in New York, London, Paris and Tokyo, Magnum Photos provides photographs to the press, publishers, advertising, television, galleries and museums across the world.

Magnum Photos – The Logo of the Company – Image via magnumphotos.com

The Idea Behind Magnum Photos

Keeping a powerful vision of artistic continuity of photography, Magnum Photos chronicles the world captured in a frame, all the places, people and events that were photographed in the last couple of decades. The most impressive aspect of this organization is the photo archive through which such a chronicle is possible – this library mostly consists of works by Magnum photographers and it is estimated to have approximately one million photographs registered there. This unprecedented and incredible archive safely holds most of the major world events and personalities from the Spanish Civil War to the present day, constantly being updated with new photos from members and owners.What makes Magnum Photos so valuable to street photography is a policy of appreciating the documentative role of photographers – this makes Magnum virtually the only organization of this type, a company dedicated to gathering works of an unparalleled sense of vision, imagination and brilliance. It also means that Magnum has been in a position to follow the development of all aspects of photography, including the street subgenre, ever since the organization was founded in the year of 1947. Studying their archive is like investigating an artistic chain with every link being an independent photo that is somehow connected to both the previous and the next one. It offers a long-lasting connection between the past and the current situation of the medium, uncompromisingly explaining how photography evolved and adapted over the years. One of the co-founders and most famous members is the aforementioned Henri Cartier-Bresson, and he described this artistic alliance with the following statement: Magnum is a community of thought, a shared human quality, a curiosity about what is going on in the world, a respect for what is going on and a desire to transcribe it visually. Other founding members of Magnum Photos were Robert Capa, David Seymour, George Rodger, William Vandivert, Rita Vandivert and Maria Eisner, all of whom founded the company with Henri Cartier-Bresson in Paris. Due to its nature and long-term commitment to gathering images, Magnum is an unavoidable stop for anyone interested in exploring the world of street photography.

Henri Cartier-Bresson – Calle Cuauhtemoctzin, 1934 – Image via finlandtoday.fi

Street Photo Meets Early Urban Art

As was said before, during the 1970s, street photography reached a level of appreciation that it never received earlier and it became both an influential and a legitimate art form. About the same time, first urban pieces as we know them today started to appear around Europe and the United States. Up until that time, graffiti was almost exclusively connected to gangs which used tagging on train cars and public walls in order to mark their so-called territories, but in the 1970s, graffiti started to be used as an expression tool for people not involved with crime. Its transformation from an illegal tool to a true underground culture was a sudden change and the public needed more than a few years to truly accept it, but early urban expression seemed to be a hand in glove fit with street photography. The two modern mediums showed that they are much stronger together and it’s not easy to find such a perfect, mutually beneficial relationship in the entire history of modern art. Urban art offered new things for street photography to shoot and randomly discover, it provided it with additional diversity. Graffiti also offered new compositional options for a street photographer – up until that point, the artist usually focused on subjects of interest, whilst the background was not as crucial and was even often blurry. The presence of an outside piece carefully placed in the background of a photo massively enrichened options placed before an artist holding the camera, giving him numerous new solutions that made the photo more enchanting. It also fit in rather nicely with the definitive requirement of a street photographer that stated he needed to work in an urban environment – since urban works is almost exclusive to such surroundings, this was just another puzzle piece fit between the mediums. In return, street photography offered the solution to early urban expression’s greatest problem – a way out of its transitory nature. No matter how good or impressive or original the urban piece was, the bottom line was that such methods of expression were illegal and they were doomed even before they were completed. However, if a street photographer was able to make an image of the piece, the act of painting over the graffiti immediately stopped being so terrifying and it started to make sense to work hard at something despite knowing it will be ultimately destroyed, since you also knew that it will be safely documented and remembered. Street photography was also attracted to the illegal nature of graffiti painting due to the adrenaline and stress urban artists experienced whilst working. Evoking such strong emotions was irresistible to a medium that was in its basis seeking to capture the true passion and honesty inside the camera’s frame. From such a mutual interest, a whole new subgenre was born and soon the term Street Art Photography was widely acknowledged.

Thomas Von Wittich – Buff – Image © Thomas Von Wittich

Street Photographer and Graffiti

Just as its older brother street photography, it took some time for urban art photo making to fully develop and establish itself as an emancipated genre. As is the case with any style or movement in art history, the process of establishing urban photography was untangling thanks to the artists who worked on the new genre – but, what differed from any other art form from an earlier period is that this new movement was required in order for urban art to survive. For example, painters of Expressionism, sculptors of Baroque or artists of Neoclassicism, none of them worked under the pressure which came with the knowledge that their work will be destroyed without compromise. Making photos out of urban works was not a choice or a commodity, but rather a necessity – it was the only possible way to save the tagged New York subways, Berlin’s murals or London’s painted brick walls. Sometimes, the person making an image of the urban piece was the actual artist himself, in other cases, the one who archived the graffiti was an amateur photographer, whilst in other times the one held responsible for the camera was a photojournalist or a full blown artist. The latter is the group that had the strongest role to play in forming the street art photography as the artists not only had the skill to get the most out of an image, but they also had an established reputation that helped in spreading the new subgenre’s principles and goals, making it seem more artistically legit. And as the new movement was evolving and attracting more attention both from photographers and audiences, urban photography started to expand in its concepts – not only was it a way of preserving a piece, now the man behind the camera was interested in other aspects like investigating the graffiti’s surroundings, capturing the atmosphere and the very process of painting such a piece, influencing the public perception which mostly considered outside artworks to be an illegal waste of materials, exploring the individual feelings and intentions of those who wish to make urban art, as well as the lengths they will go through in order to do so. This, of course, did not happen overnight. Many photographers worked hard and long at developing such concepts, and in order to prevent the utter destruction of their fellow artists’ work, they specialized in documenting graffiti in its urban contexts. We will now present you with the stories of the most crucial among them, the ones without whom the subgenre of street art photography would not only be a lot different from what it looks like today but would have probably never even happened.

Mark Rigney – Jorge Rodriguez Gerada – Photo © Mark Rigney

Martha Cooper

What better person to start this list than the one who was there from the very beginning of urban painting and is still active today? Martha Cooper is an American photographer from Baltimore who became noticed for her remarkable work of documenting the 1980’s New York City graffiti scene. She was a daughter of a camera store owner, so naturally, her love for photography has developed rather early on. When she was about the age of three, her father gave her the camera and the two strolled down the neighborhood in search of exciting shooting opportunities. As you may notice yourself, such an approach Cooper was exposed to from the beginning of her life is the heart and soul of street photography – something this artist adopted gladly, letting it dictate every creative decision of her career. During the aforementioned circumstances of the 1980s, Martha was one of the photographers who witnessed the birth of modern urban expression. Besides her natural instinct for urban photographing, the illegal aspect of graffiti making is the very thing that attracted her to the outside scene. She began her ventures by documenting subway tagging in New York as she was introduced to the inner circle of the graffiti painting community through a friend artist HE3. Soon after that, Cooper met Dondi, one of the biggest stars of artistic tagging back then. Her work was not only extensive in nature, but she was also the first one to follow the sprayers on their subway tours, photographing everything and preserving all the works in their natural, full context. There are both black and white and in color pieces of her work from that period, but what all her photos display is a natural talent for perfect timing and composition. It’s remarkable that none of her images are tempered with after they are taken. In the year of 1984, all of her works were published in a famous photo collection titled simply as Subway Art – this extensive portfolio was a crucial milestone in photography which defined the goals of the new subgenre. Other books published by Martha Cooper are Hip Hop Files, R.I.P. New York Spraycan Memorials and From Here to Fame, but none of them can rival the impact Subway Art had on the artistic community. Martha Cooper is also credited as one of the pioneers of defending the artistic concept of graffiti, which is even more impressive when you consider that back then outside works were treated as vandalism: I tell people to check out all the enormous ugly, mass-produced ads covering whole sides of buildings and ask why they aren’t more concerned about those. Graffiti can be art and vandalism at the same time. I’m not a fan of every tag on every surface but I do appreciate illegal work in unusual spots. At least with graffiti, you know that a person was painting by hand, and I will always take anything handmade over mass-produced. To this day, Martha Cooper remains as one of the most praised artists to ever deal with contemporary street photography and urban art documenting.

Martha Cooper – NYC Subways – Image via instagrafite.com

Henry Chalfant

Another important photographer that helped establish both early urban art photography and subway graffiti painting is Henry Chalfant, a New York-based urban photographer who co-authored Subway Art with Martha Cooper. Chalfant actually emerged onto the art scene as a sculptor back in the 1970s but shifted to photography and film after he found himself attracted to the subcultures of hip-hop, breakdance and graffiti. Both his early and mature works show great talent for angles and the commitment he showed to documenting graffiti tags paid off greatly – his photographs record hundreds of original artworks that have long since vanished and thanks to his tirelessly made archive, we are now able to analyze the development of early street art to the smallest detail. Chalfant mainly focused on the most popular location for graffiti back then – the subway cars. He documented the trains with a strict approach of defined compositions and 90-degree angles, making his work quite fitting for an archive. Henry’s portfolio is quite similar to that of Martha Cooper and he as well dabbled in street photography in a more traditional sense of the genre. As was clued at before, Henry Chalfant also dedicated himself to documenting alternative cultures on film. His most recognized and influential street art film is Style Wars, a documentary movie which was awarded the Grand Prize for Documentaries at the 1983 Sundance Film Festival. Today, Henry Chalfant is one of the leading authorities on New York subway art and other aspects of urban youth culture that emerged back then.

Henry Chalfant – Team Rex – Image via teamrex.org

Jürgen Große

German photographer Jürgen Große made a reputation for himself by documenting urban art found in the city of Berlin. Most of his work can be found in an extensive portfolio book titled Urban Art Photography – it presents the viewers with images of the street art scenery of Germany’s capital from a never before seen angle. The amount of care and attention Jürgen Große incorporates into his work is unrivaled and what makes him stand out is his way of handling the context of the urban piece, showing great respect for this often overlooked aspect of the graffiti technique. Successfully seizing this interplay, his images serve as a permanent documentation and a time capsule for the street art pieces he chooses to use as a subject matter – which is extremely useful when you consider the dynamics and constant changing of images Berlin’s scene is so famous for. To match that intensity, Jürgen’s images are also really dynamic and extremely adventurous, maybe even best described as playful. Famed for their various angles, Große’s documentations are so systematically intelligent and organized that reading through his Urban Art Photography is a true joy for anyone interested in discovering either urban painting or street art photography. The planned and purposeful observation he showed so far is a perfect fit with the ideas of street photography and the natural talent for capturing the context of a street piece makes him important reading material for anyone investigating Europes street art photography.

Jürgen Große – An Untitled Photo From Berlin – Image via just.de

Nils Müller

Nils Müller is another German street art photographer on this list, but what makes him unique is his background, which is quite different than the one of Jürgen Große. Müller was himself a talented graffiti artist in his youth he spent in Cologne and learned first hand just how traumatic losing his work was, regardless of who or why was painting it over. In order to preserve his own graffiti, Nils decided not to hire or contact someone skilled in the street art photography department, but rather to attempt to shoot his own images instead. By doing so, he hoped he would give his work immortality – or at least the illusion of permanence. As he had no prior experience in photography, Müller had no choice but to learn everything on his own. He decided to focus more the act of creation as he knew how important the emotional tensions surrounding street art making is. Soon, he started to photograph other artists doing their own work, continuing to put the accent on the process of creation. This personal approach makes Nils quite unique as Müller tried to portray the characters and personalities of graffiti painters. He made a practice of following them from A to B, recording every step of the way a street artist would take. Eventually, Müller stopped making urban art but continued to document the works of younger street artists, making images praised for their thrill and aesthetic value. Not venturing from the urban art settings, Müller also worked on staged photography which as well concentrated on graffiti authors. Documenting the process behind painting graffiti on trains, Nils published two books in his time: Bluetezeit – Prime Time of my Life and Vandals.

Nils Müller – Untitled – Image via counterparts.de

Alex Fakso

Italian photographer Alex Fakso commenced his artistic journey in the early 1990s as a skateboard photographer who was also a casual graffiti writer. After he found out how street art photography is able to impact the public, Fakso was immediately attracted to this subgenre and its rebellious nature. He was only sixteen years of age but showed impressive initiative and boldness necessary for street art photography. Due to his friendships and acquaintances as a skateboarder, Fakso was in a position to easily start following urban painters while they did their thing – soon Alex embarked upon a personal quest of recording the entire process of graffiti writing in both train and subway terminals. To become even better at what he wanted to do, he registered as a student of the Arts Institute in Padova and learned graphic design and traditional photography. Like many of the artists on our list, Fakso also preferred to concentrate on the process of making an urban art piece, with the actual graffiti seldom being the main subject of his images. Alex also did not shy away from presenting the faces of the artists, which was quite bold of both him and the subject. Most of his photos are black and white and show shots of the street artist preparing to paint the graffiti, hopping over a fence and running away from the authorities, or posturing with the equipment – he seeks to catch the emotions and difficult circumstances graffiti writers have to go through during their creative processes. Prior to the invention of the digital photography, Alex Fakso was one of the rare people to do street art photography in Italy as many steered clear of the genre because of the illegal nature and sheer difficulty of carrying so much equipment. Over the course of his career, Fakso collaborated with many fellow street art photographers, including Martha Cooper with whom he held an exhibition. Fakso’s work is documented in his two published books titled Heavy Metal and Fast Or Die, both of whom display his remarkable imagery.

Alex Fakso – Untitled – Image via newyorker.com

Ruedi One

Ruedi One is an alias of a German photographer who also had experience as a street artist in his background which allowed him to become a better documentative photographer of the urban scene. He always felt a strong need to document his own works and at one point in his life, this simply took precedence over the actual making of urban art. Since he primarily wanted to make photos of street art, by far a simpler way was to make images out of other artist’s work, allowing Reudi One to focus on the process of preserving the pieces within the camera’s frame. By his own claim, that passion, obsession and even addiction is what made him a good photographer. Ruedi One has been active for almost ten years now and enjoys a stellar reputation of an elite urban art photographer. Just like Alex Fakso, this artist also focuses his efforts on making the viewer feel as if he is present on the actual spot and at the moment the street piece was made – Ruedi One’s images are full of tension, danger and adrenaline common for the process of illegal graffiti painting. Speaking in terms of technique, Ruedi One works exclusively in a black and white style and his fantasitc portfolio was made on the streets of New York City, Sao Paulo and Hamburg.

Ruedi One – Untitled – Image via stycdn.net

JUST

Another Berlin-based artist on this list, Boris Niehaus (a.k.a. JUST) is one of the most influential street art photographers in Europe. He has been active on the urban art scene since the year of 1999 and has authored some of the most outstanding photographs of the street genre. JUST attempts to find the perfect balance between documenting the pieces considered to be the highlights of the scene and portraying artists who made the pieces happen. The reason he is as successful as he is may be found in the fact JUST has an incredible amount of friends and contacts in the urban scene, which pretty much means that he is the first person who finds out when new graffiti has appeared in Berlin. Always a step ahead of the competition, JUST is now widely regarded as a crucial cog of German urban photography. Brad Downey, Mark Jenkins, Blu, ZEVS, FAITH 47, Dave the Chimp, Doma, DAIM, D•Face, EVOL and Nomad – these are just some of the names that managed to find their way into Boris Niehaus’s portfolio. JUST’s unconventional photographs are so full of energy and passion, which is undoubtedly due to the fact he intimately knows the artists he shoots with his trusted camera. This familiarity and closeness is the essence of his photographs. JUSTʼs work can be found in numerous books and exhibition catalogs, as well as various magazines and newspapers such as ART, Modart, Backspin, Zitty, FAZ, Spiegel and The New York Times.

JUST – Rooftop Berlin, 2010 – Image via JUST

Keegan Gibbs

Whilst artists like Martha Cooper tried to balance the precedence between the artists and the finished artwork, putting an additional accent on the process of painting the actual piece, Los Angeles-based photographer Keegan Gibbs unquestionably prioritizes the artists over the art. Focusing on the actual painter, Gibbs follows the best urban painters of Los Angeles, climbing with them onto buildings, rooftops and billboards. Such an approach heavily influenced his urban photography and gave it a strong biographic note, simultaneously enabling the viewer to feel more present and more emphatic towards the graffiti painter. Substituting the adrenaline for reasoning and personality, the works of Keegan Gibbs allowed the artist to tell their own story. With a natural talent for composition, his images are also accompanied by essays and stories of nights out with the artists, making his entire portfolio seem like a true biography. Since most of his images are made during the night, Gibbs’s work is quite adventurous, and due to the fact he skillfully hides the faces of his subjects, his work was often characterized as mystic. An interesting fact is that Keegan was terrified of heights, but in order to get the most out of his photos, he was forced to deal with his fear of altitude. Gibbs followed many representatives of the Los Angeles street scene, but the arguably most successful works came from accompanying the graffiti artist Augor.

Keegan Gibbs – Revok – Image via obeygiant.com

JR

Proudly standing as not only one of the most successful photographers of modern time but also as the most intriguing one due to his hidden identity, JR is one of the walking legends of the urban art scene. This French artist is not primarily famous for his photographs of street pieces but rather for his urban artwork which is unparalleled in its creativity and unlike anything ever recorded in the history of art. His method is quite unique, as he takes pictures of people, pastes them on the walls and roofs of public surfaces and then takes a photo of the hanged images, making use of what he likes to call the largest art gallery in on the planet – the streets. This ensures that JR attracts the attention of people who are not typical visitors of museums or galleries, which is one of the main features and advantages offered by urban art. The way JR is able to use architecture is simply remarkable and it’s impossible to even compare him with anyone else, regardless of when they used to create their art. His numerous projects, such as Inside Out, Women are Heroes, Face2Face and 28 Milimetres, display a strong note of combined elements belonging to both photography and urban scene. For example, the Face2Face project was the biggest illegal exhibition ever held and it consisted of monumental portraits of both Israeli and Palestinian men and women, positioned so that they face each other and prove that they are fundamentally alike. The show was displayed in eight in Palestinian and Israelis cities, on both sides of the notorious Separation wall and JR documented them with vigor and style. Simultaneously being an artist, photographer and an activist, JR is an extraordinary figure of the urban scene. Although much of his work is technically illegal, JR managed to win the TED Prize, an award given to someone who aims to change the Earth with his artworks. Despite his method being a fantastic mix of art and act, his place on this list is secured due to JR’s principles of documenting his journey, as well as his routine of hanging the said photos on the walls of numerous metropolises. Exclusive documenting of his own works also makes him a unique photographer, as JR does not take pictures of other people’s art.

JR -Captured Ecran, 2010 – Image via thatcreativefeeling.com

Thomas von Wittich

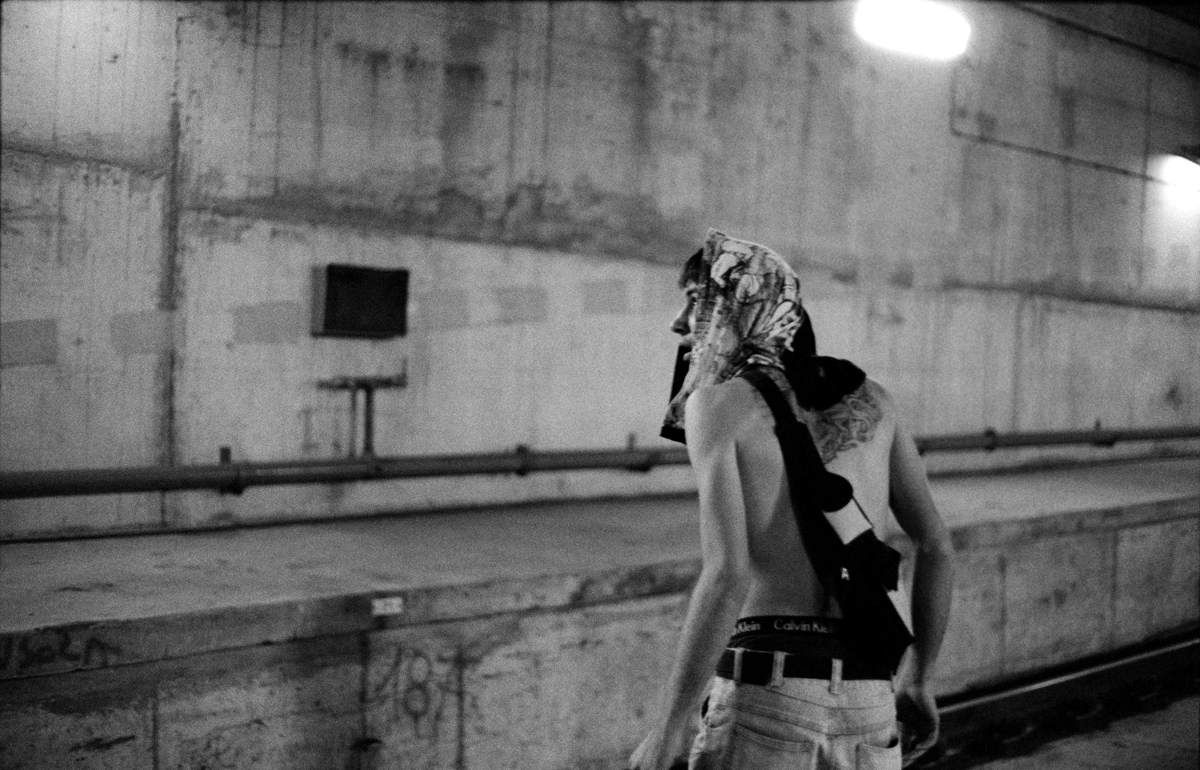

One of the youngest and most promising photographers on this list is Thomas von Wittich, an artist born in 1983 in West Germany, essentially appreciated for his shots of contemporary artists from his nation’s scene. He started out as a graffiti painter himself, but just like many of his photographer colleagues on this list, Thomas as well forsook his urban expression in order to make images and document other people’s works. Thomas von Wittich also has the most troublesome past of all the artists on this list – he left home when he was only 13 years old. In order to support himself and somehow make ends meet, he began working in the meatpacking industry. It was not until he started to take pictures of music concerts with his trusted Leica R4 that things would start to look up for Thomas. Since he was an urban artist in his free time, von Wittich would document his own graffiti and keep a personal archive, not having a clue that this hobby would one day make him famous. After some time dedicated to practicing, a teacher at his school started to notice the talent and potential of Thomas von Wittich. Subsequently, he was handed an opportunity to enter the field of professional photography and from then on dedicated most of his efforts to taking photos of outside pieces. Under the guidance of the American pop-photographer Jeffrey Delannoy, Thomas von Wittich perfected his methods and studied the classical black and white photography of Parisian streets from the 1940s to the 1960s, basing his expression on the medium’s greats. Much of his work can be associated with Henri Cartier-Bresson and the concept of the decisive moment, as Thomas seems to chase that perfect split second that must be captured by any means necessary. All of the efforts put into developing eventually turned Thomas von Wittich into one of the most influential urban photographers to date, the one who successfully blends reporting, portraiture and directing in order to document the streets, instilling excitement into anything making its way into his portfolio.

Thomas Von Wittich – MissTake – Image © Thomas Von Wittich

Jaime Rojo

Jaime Rojo is a photographer who’s both a co-founder and an editor of Brooklyn Street Art, an organization dedicated to tracking the creative spirits of the urban environments, which effectively makes it a crucial part of urban photography and its community. Besides documenting the actual urban pieces of art, BSA is also concentrating on shooting the studios of urban artists and galleries of New York City who appreciate and display the pieces of this medium. Much of the achievements of BSA is due to its founders Steven P. Harrington and Jaime Rojo, responsible for many artistic decisions and courses of the organization concerning the aspect of urban imagery. The idea behind this company is to closely follow new hybrids, new techniques and new mediums that expand the definition of urban expression. As urban painting evolves and develops, BSA is dedicated to observing such adaptation and document the changes, as well as keeping tabs on how the said alterations affect popular culture and the rest of the art scene as a whole.

Jaime Rojo – Occupy Wall Street (Left) / SOHO, NYC (Right) – Images © Jaime Rojo

Mark Rigney

Yet another important representative of the urban picture-taking and its community, Mark Rigney is an Irish-born photographer, designer and blogger currently working and living in East London. For over ten years now, Rigney has been documenting the ephemeral art on the streets of London, effectively becoming a very resourceful urban art photographer due to the dynamics of the scene present in England’s capital. His graffiti photography is regularly featured in the UK’s magazine VNA, as well as having appeared in various books including Untitled 111 and both tomes of The Art Of Rebellion. Such recognitions make Mark one of the most successful photographers of the street and definitely worthy of our list. His sense of timing, selections of perfect angles and compositional solutions helped Rigney build an impressive reputation around his name and become a key figure of the UK’s urban scene. As was clued earlier, Mark is also an editor and founder of Hookedblog, one of England’s leading urban expression websites – established in 2005, it serves to this day as a great urban art resource and a perfect place for Mark to output his work.

Mark Rigney – Alexis Diaz – Photo © Mark Rigney

Modern Circumstances of the Genres

So, as we’ve entered the third millennium, what’s the place reserved for the likes of street photography and urban art documentation? Since all of the artists from the list above are still active to this day, we can rest assured that urban photography is in safe hands. At the end of the day, that subgenre is completely chained to the quality of urban art and as long as that scene continues to evolve down interesting courses and flourish, there will always be talented and dedicated individuals who can successfully document them. However, the situation surrounding regular street photography is more interesting – the 21st century provided mankind with an incredible technological boost, making sure that literally anyone can possess the devices required to make a visually stunning photo. Sure, technological advancement also heavily affected this type of photography, but with its goals strictly set and defined, this subgenre is not in trouble of losing its course anytime soon.

Street photography, on the other hand, seems to be yet again the victim of its freedom and deceptively loose rules. With everybody being able to afford top of the line devices and snap pictures around the towns they live in, it looks as though the entire medium becomes a small pond full of crocodiles and that it will easily become too ordinary to be noticed. This concern, although widespread, is far from a real threat. Even in its most modest and primitive beginnings, street photography was unbreakably connected to technology, always choosing to use the most advanced devices at its disposal – so the modern cameras now available are actually quite natural for this genre. To street photography, our modern situation is nothing but an irrelevant circumstance to which it will yet again adapt as it always had, it only provides it with better accessibility and more material. All we might ever need in order to find the best street photography is a better filtration system due to so many photographers being active, which can only lead to more diversity and fresh ideas contributing to the genre’s greatness.

To summarize, street photography of the 21st century merely adapted to new contexts and circumstances, while continuing to place emphasis on urban public settings, photographer’s intuition and candid nature of the style – the inherent trio which makes street photography genuine and true to its heritage. And these key aspects can not be endangered by any amount of technological advancement or overusage that define the current state of photography scene.

Written by Andreja Velimirović